Should the Poems Be the Poet's Legacy?

In Christian Wiman's editorial, In the Flux That Abolishes Me, from the March 2006 Poetry Magazine (which I just got to yesterday), he talks about receiving manuscripts for submission, written by people who are now dead. The family or executors find poetry left behind, and send it in for hopeful publication, or to answer the question of whether the work is publishable. As we who write can imagine, the great majority will not make it into such a magazine.

In Christian Wiman's editorial, In the Flux That Abolishes Me, from the March 2006 Poetry Magazine (which I just got to yesterday), he talks about receiving manuscripts for submission, written by people who are now dead. The family or executors find poetry left behind, and send it in for hopeful publication, or to answer the question of whether the work is publishable. As we who write can imagine, the great majority will not make it into such a magazine. Wiman notes that, although unpublished, these poems may get passed down generations. His article ends with this statement:

Perhaps one of these very bundles will makes its way into our offices again in a hundred years, when we shall all be changed.

In the middle of this article, Wiman discusses how most poets who were published in their lifetimes, have readerships that dwindle yearly following their deaths. While making this point, he makes the following statement that struck me:

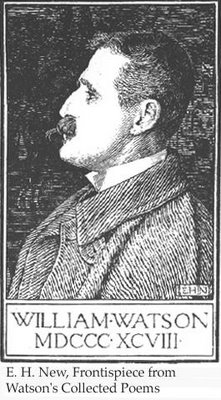

Were their labors "justified"? You might as well ask that question of Robert Carleton Brown, Lydia Huntley Sigourney, William Watson, each of whose work, famous in its day, now rots unread in a few anthologies.

Lydia Huntley Sigourney . . . Just two days ago, I featured her poem "Pocahontas" in the post: "Pocahontas" by L. H. Sigourney, 1841. Besides the poem being a good read, it was a big part of the catalyst behind the legend of Pocahontas becoming as widely known as it is today. For instance, a Google search for Pocahontas tonight yields over 8 million results (outdoing American Idol Taylor Hicks by about 3 million, and leaving Jack Kerouac in her dust by 5 million).

Lydia Huntley Sigourney . . . Just two days ago, I featured her poem "Pocahontas" in the post: "Pocahontas" by L. H. Sigourney, 1841. Besides the poem being a good read, it was a big part of the catalyst behind the legend of Pocahontas becoming as widely known as it is today. For instance, a Google search for Pocahontas tonight yields over 8 million results (outdoing American Idol Taylor Hicks by about 3 million, and leaving Jack Kerouac in her dust by 5 million).Wiman is correct, however. We are not reading Sigourney right now. But her work is not rotting. Rather, it is preserved for when it comes time for a revisit or a possible, maybe likely, resurgence. Furthermore, Sigourney, as a poet, changed our culture. How often a poem gets read in future generations, is only one measure of the staying power of a poet. The impact can be far more important.

This can be an attitude adjustment for the big poetry ego. My name may not live on--probably won't. More important, then, is the social effect that I work toward. Even though, for instance, Kerouac is not attributed with so much of our daily thoughts and behavior, he sure changed them. The world would not be the same place, moment to moment, if it were not for him. In a smaller, Pocahontas way at least, the world would not be the same were it not for L. H. Sigourney. But historically, that is still big-time compared to the other 99 percentile of us poets. We'd do well to get off the idea that we need to write poetry that will "last"--or, rather, remain in vogue.

This can be an attitude adjustment for the big poetry ego. My name may not live on--probably won't. More important, then, is the social effect that I work toward. Even though, for instance, Kerouac is not attributed with so much of our daily thoughts and behavior, he sure changed them. The world would not be the same place, moment to moment, if it were not for him. In a smaller, Pocahontas way at least, the world would not be the same were it not for L. H. Sigourney. But historically, that is still big-time compared to the other 99 percentile of us poets. We'd do well to get off the idea that we need to write poetry that will "last"--or, rather, remain in vogue.A poem good for today only, is a good and worthy poem. An example is John Hegley's poem "Zinner the sinner?" in Tuesday's Guardian. It may not last the month.

Because we each have some effect anytime we share our work, it is better to keep the negative out if possible. Part of the drawback to Sigourney's poem "Pocahontas" is that, in the form that became publishable, she wove in components that fostered prejudice against Native Americans--even if it was her hope that we would certainly read beyond these afterthoughts.

William Watson, wrote many of his poems for his time, which is a good reason we do not read him that much today. The two poems below inform us on this topic, however, today.

by William Watson

The River

I

As drones a bee with sultry hum

When all the world with heat lies dumb,

Thou dronest through the drowsèd lea,

To lose thyself and find the sea.

As fares the soul that threads the gloom

Toward an unseen goal of doom,

Thou farest forth all witlessly,

To lose thyself and find the sea.

II

My soul is such a stream as thou,

Lapsing along it heeds not how;

In one thing only unlike thee,--

Losing itself, it finds no sea.

Albeit I know a day shall come

When its dull waters will be dumb;

And then this river-soul of Me,

Losing itself, shall find the sea.

. . .

.

by William Watson

To a Poet

Time, the extortioner, from richest beauty

Takes heavy toll and wrings rapacious duty.

Austere of feature if thou carve thy rhyme,

Perchance 'twill pay the lesser tax to Time.

. . .

.

3 Comments:

We'd do well to get off the idea that we need to write poetry that will "last"--or, rather, remain in vogue.

Cool post, Bud. I tend to agree with this. In fact, I would go even so far as to say we need to let go of the idea that poetry should be written for any kind of an audience at all (save the poet him- or herself... and even then... ;-) And ironically, this will probably lead to poetry that has a better chance of "lasting." Think of Emily Dickenson, the classic example. I wonder how many other Dickensons there are out there, the poems "rotting" in boxes in attics. As long as the mice don't use them for bedding, they're lasting just fine, though.

Hi Peter,

Well put.

Thanks very much for stopping by and leaving such a good note.

Bud

That Watson fella, he sure uses some beauuuuuuuuutiful words, he must be the real deal. That river poem there, that had some pretty words, too.

Take the intelligence out of Tennyson and substitue cleverness while making the music more plebeian and you have a rude approximation of Mr. Watson, IMNSHO

Post a Comment

<< Home