Poetry for Your Guts

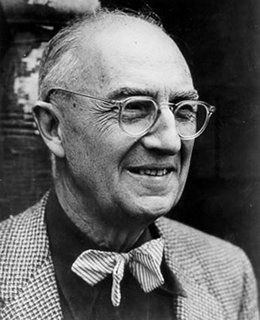

Into his poem In Memory of W. B. Yeats, W. H. Auden wrote these two lines:

Now Ireland has her madness and her weather still,

For poetry makes nothing happen: it survives

But he also wrote these two in:

The words of a dead man

Are modified in the guts of the living.

A poem can make nothing happen--and neither can a dead man. The words from poems, transferred into the guts of we who are living, change us, and thus change our actions, because they affect decisions we make.

Into the poem Asphodel, That Greeny Flower, William Carlos Williams wrote the following lines:

It is difficult

to get the news from poems

yet men die miserably every day

for lack

of what is found there.

People will die every day anyway. Without poetry, we die more miserably. Here is another reason to get poetry into our guts.

In this blog entry, I will look at a couple cases of poetry being used to make social change within cultures. A cross-cultural argument is made hopefully in the presentation, that we in our guts can be affected by circumstances we come to know of in other cultures, as others model change, potentially positive change for us. In other words, we are truly one big world culture, one big WE, yet a WE with subcultures or sub-WEs we can put to use for the sake of objectifying what is usually subjective.

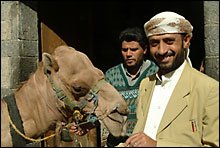

Let's begin in Yemen. Possibly nowhere else in the world, is poetry already in people's guts as much as in this country. From James Brandon's recent article in the Christian Science Monitor, In poetry-loving Yemen, tribal bard takes on Al Qaeda--with his verse, come these excerpts:

Let's begin in Yemen. Possibly nowhere else in the world, is poetry already in people's guts as much as in this country. From James Brandon's recent article in the Christian Science Monitor, In poetry-loving Yemen, tribal bard takes on Al Qaeda--with his verse, come these excerpts:~~

"Other countries fight terrorism with guns and bombs, but in Yemen we use poetry," says Mr. [Amin al-]Mashreqi later. "Through my poetry I can convince people of the need for peace who would never be convinced by laws or by force." . . .

"Yemen has turned to poets because they are able to speak to diverse groups of people who the literati and the elite cannot reach," explains W. Flagg Miller, professor of Anthropology and Religious Studies at the University of Wisconsin who has studied Yemeni poetry for about 20 years. . . .

"There is a long tradition of leaders turning to poets right across the Arab world," explains Dr. Miller. "The prophet Muhammad himself worked with a poet, Hassan ibn Thabit, to spread the word and compose poetry against other poets and tribes who refused to acknowledge Islam." . . .

And although Yemen has used force to tackle Al Qaeda cells and rebel groups, Mashreqi's poems also fit into Yemen's wider strategy of defeating Islamic extremism by appealing to their countrymen's sense of pride, honor, and patriotism.

O men of arms, why do you love injustice?

You must live in law and order

Get up, wake up, or be forever regretful,

Don't be infamous among the nations

The poems, however, also robustly argue that carrying out terrorist attacks in Yemen will succeed in scaring away much-needed foreign investment and tourism--an argument that few impoverished Yemenis can dispute. . . .

~~

For commentary on this subject beyond the Christian Science Monitor's article, see Linda Sue Grimes's Fighting al Qaeda with Poetry at BellaOnline.com. And by the way, poetry is currently being used in Yemen to fight the high illiteracy rate among women. For more on this, see Kim A. O'Connell's In Yemen, Fighting Illiteracy Through Poetry in the National Geographic. My concern is to extract and show from these articles and poems, how it is that poetry effects our guts, or at least how it is called upon to do so.

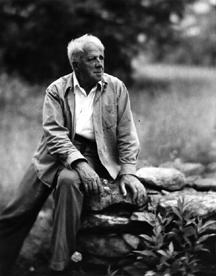

A most common case of a poem being so called upon in Western business and self-improvement cultures, to affect people, and thus effect change, is the reading of Robert Frost's The Road Not Taken (audio on link's page). Interestingly enough, Frost's Mending Wall is more often used just for its "Good fences make good neighbors" quote, to inspire the listener to build a fence or let a fence be erected, even when the poem may suggest something else. But enough people say that their lives have been effected by such a reading of "The Road Not Taken," for us to put this entire poem into the category of one that effects social change, even though we may not be able to say specifically that even one good new road has been built because of it, or that one family has been happier for it, that any given or particular good occurrence has come of it. We can, however, surmise that something good could have, so must have happened, because of Frost's poem.

A most common case of a poem being so called upon in Western business and self-improvement cultures, to affect people, and thus effect change, is the reading of Robert Frost's The Road Not Taken (audio on link's page). Interestingly enough, Frost's Mending Wall is more often used just for its "Good fences make good neighbors" quote, to inspire the listener to build a fence or let a fence be erected, even when the poem may suggest something else. But enough people say that their lives have been effected by such a reading of "The Road Not Taken," for us to put this entire poem into the category of one that effects social change, even though we may not be able to say specifically that even one good new road has been built because of it, or that one family has been happier for it, that any given or particular good occurrence has come of it. We can, however, surmise that something good could have, so must have happened, because of Frost's poem.Is that, though, the best Western society can do with poems? Can't we in the West, like Yemenis, call upon a poem now and then, to make change for the better? The answer to such a general question is, "Of course." To mind, comes the circumstance of a lawyer arguing for a client, or a legislator arguing for a law--using the ring of poetry to change the guts of listeners, to persuade for the good of their respective causes. Another situation is a man asking a woman to marry him. So we have the utility of poetry, poetry as rhetoric. Let's toss in Allen Ginsberg's Howl as a poem we know changed some of our guts in this way.

An article Alex Beam wrote for the Boston Globe, appears in the International Herald Tribune today, Meanwhile: Killing me softly--A lobster tale. Beam writes:

Lewis Carroll's poem "The Walrus and the Carpenter" is probably the greatest seafood saga of modern times, and a prescient tribute to the notion of "humane" degustation.

Here is that poem from Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There:

~~~~

The Walrus and The Carpenter

The sun was shining on the sea,

Shining with all his might:

He did his very best to make

The billows smooth and bright--

And this was odd, because it was

The middle of the night.

The moon was shining sulkily,

Because she thought the sun

Had got no business to be there

After the day was done--

"It's very rude of him," she said,

"To come and spoil the fun!"

The sea was wet as wet could be,

The sands were dry as dry.

You could not see a cloud, because

No cloud was in the sky:

No birds were flying overhead--

There were no birds to fly.

The Walrus and the Carpenter

Were walking close at hand;

They wept like anything to see

Such quantities of sand:

"If this were only cleared away,"

They said, "it would be grand!"

"If seven maids with seven mops

Swept it for half a year.

Do you suppose," the Walrus said,

"That they could get it clear?"

"I doubt it," said the Carpenter,

And shed a bitter tear.

"O Oysters, come and walk with us!"

The Walrus did beseech.

"A pleasant walk, a pleasant talk,

Along the briny beach:

We cannot do with more than four,

To give a hand to each."

The eldest Oyster looked at him,

But never a word he said:

The eldest Oyster winked his eye,

And shook his heavy head--

Meaning to say he did not choose

To leave the oyster-bed.

But four young Oysters hurried up,

All eager for the treat:

Their coats were brushed, their faces washed,

Their shoes were clean and neat--

And this was odd, because, you know,

They hadn't any feet.

Four other Oysters followed them,

And yet another four;

And thick and fast they came at last,

And more, and more, and more--

All hopping through the frothy waves,

And scrambling to the shore.

The Walrus and the Carpenter

Walked on a mile or so,

And then they rested on a rock

Conveniently low:

And all the little Oysters stood

And waited in a row.

"The time has come," the Walrus said,

"To talk of many things:

Of shoes--and ships--and sealing-wax--

Of cabbages--and kings--

And why the sea is boiling hot--

And whether pigs have wings."

"But wait a bit," the Oysters cried,

"Before we have our chat;

For some of us are out of breath,

And all of us are fat!"

"No hurry!" said the Carpenter.

They thanked him much for that.

"A loaf of bread," the Walrus said,

"Is what we chiefly need:

Pepper and vinegar besides

Are very good indeed--

Now if you're ready, Oysters dear,

We can begin to feed."

"But not on us!" the Oysters cried,

Turning a little blue.

"After such kindness, that would be

A dismal thing to do!"

"The night is fine," the Walrus said.

"Do you admire the view?

"It was so kind of you to come!

And you are very nice!"

The Carpenter said nothing but

"Cut us another slice:

I wish you were not quite so deaf--

I've had to ask you twice!"

"It seems a shame," the Walrus said,

"To play them such a trick,

After we've brought them out so far,

And made them trot so quick!"

The Carpenter said nothing but

"The butter's spread too thick!"

"I weep for you," the Walrus said:

"I deeply sympathize."

With sobs and tears he sorted out

Those of the largest size,

Holding his pocket-handkerchief

Before his streaming eyes.

"O Oysters," said the Carpenter,

"You've had a pleasant run!

Shall we be trotting home again?'

But answer came there none--

And this was scarcely odd, because

They'd eaten every one.

~~~~

Beam, however, is not pro-"humane degustation" in the case of raising lobsters. He goes on to say:

Wouldn't it be great if we could just wait for trees to fall down so we could build houses? Wouldn't it be great if millions of chickens and cattle could be convinced to sign up for voluntary euthanasia programs so we could eat meat? Wouldn't it be nice if those nasty insurgents in Iraq would just come talk to us over some Organic and Fair Trade Certified Monkey King Jasmine Green Tea, always available at you- know-where? What a wonderful world it would be.

He is saying, "Screw it," let's not think of the animals. We'd have to think of the lives of chickens, tree, and cows in that case. The problem he is having, is that poems such as Carroll's have modified our (and obviously his) guts, along with religious teaching about boiling a kid in its mother's milk, and Native Americans praying to thank the animals they have killed for food, knowing and accepting the animal spirit into their own.

Even still, there is a sort of graveyard humor that comes through any meat-eating culture. Here is the same sentiment about trickery as expressed in Carroll's work, showing up in an earlier Cree Narrative, as translated by Brian Swann in his Wearing the Morning Star: Native American Song-Poems:

~~

Trapping Song

Trapping SongThe animal says

Is this where we play?

Is this where you are playing?

~~

At times in our history, we have had to eat animals, just as we have had to dig to eat roots, and just as we have had to go to war, just as we have had to flee calamities. Poetry can bring us back to at least respect life and respond to suffering.

About 25 years ago, I was asked to get signatures on a petition to ban unnecessary animal testing at the local university. The number of signatures I received was well into the hundreds. Not one person who was asked, did not sign the petition. Consensus. How could that be? The operative word is "unnecessary." But the heart of the issue is that we each have a significant compassion for animals, whether vegan or avid hunter.

Maybe, as Native Americans have made it important to find out about the lives of the animals they eat, others of us can at least find out about the companies we buy food from. How do their suppliers treat the animals? How are the animals raised?

This type of thinking opens a whole can of worms. How many of us buy chocolate from companies which are supplied through child slave labor? How many of us buy products from companies that pollute the waters? On the other hand, which companies are actively involved in communities in positive ways? Which ones inspect the farms that supply them?

This type of thinking opens a whole can of worms. How many of us buy chocolate from companies which are supplied through child slave labor? How many of us buy products from companies that pollute the waters? On the other hand, which companies are actively involved in communities in positive ways? Which ones inspect the farms that supply them?Going back to the situation in Yemen, the message in Mashreqi's poetry is for peace. Any one of us, who comprehends even partially what he is doing, is all for it. Consensus again. His poetry is getting into the foundation of our humanity, and so getting into all of our guts--even though, yes, he is encountering resistance. These human truths naturally modify our guts, and can be found in poetry from all times and cultures. Through these truths, we have our consensus, and movement toward positive change.

1 Comments:

Loved reading thiis thank you

Post a Comment

<< Home